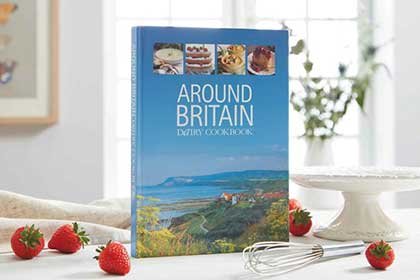

For a small nation, the topography of Britain is immensely varied. This fertile land yields the ingredients that have influenced our gastronomic heritage. From the orchards of the South East to the lochs of Scotland, each region harvests its own food and creates its own dishes.

The following regional guides are taken from Around Britain cookbook.

Scotland

Scotland is a country with many contrasts. Life in the lush meadowlands of the southern Borders has always been different from that on the harsh bare hills of the Grampians in the north, or from that on the fiercely independent islands scattered in the cold, grey North Sea.

With so many islands and its ragged coastline, the sea has long provided food for the Scottish diet. The busy ports of Peterhead and Aberdeen continue to unload large catches of herring, haddock, mackerel, halibut, sole and cod, while salmon and trout are still caught wild but also reared in giant fish farms in fresh or seawater lochs. Lobster and shrimp are caught off the Borders coast, while the Western Isles also supply scallops and winkles.

Long hours working outside in the cold and wet instilled a need for filling, hearty fare, best illustrated by the Scottish love of breakfast porridge: nutritious enough to satisfy the appetite until lunchtime, and usually flavoured with salt (though honey is not frowned upon). Similarly comforting are Scottish soups such as Scotch broth (mutton and pearl barley), cock-a-leekie (boiled fowl) (page 31) and cullen skink (Finnan haddock with potato) (page 28).

Oats have long been a mainstay of the Scottish diet, good for thickening stews and soups and grown because the crop can withstand poor soil and harsh weather. However, the milder climate and more fertile ground elsewhere enable Scotland to produce vast quantities of soft fruits, such as raspberries and strawberries. The sweet and the savoury unite in the Scottish love for baking a huge variety of cakes and biscuits, famous examples including the almond-topped Dundee cake (page 90), the rich, black bun fruit cake, bannocks (oat and barley biscuits cooked on the griddle), and melt-in-the-mouth buttery shortbread (page 73).

The Scottish moors and mountains also provide a wide selection of meat: sheep thrive on the rough slopes, and Scottish beef fed on the lush lowland grass is renowned the world over. An abundance of game inhabits the moors and forests, with deer (venison), grouse, partridge and pheasant being the best known. Perhaps the most famous Scottish meat dish is the haggis, the boiled and minced insides of a sheep mixed with beef suet and oatmeal then boiled or baked in the bag of the sheep’s stomach (page 174). It tastes a lot better than it sounds! Dairy farming has long flourished throughout Scotland, and recently cheese making has been revitalised with the manufacture of a wide range of traditional and contemporary home-produced cheeses in addition to the popular Scottish Cheddar.

Although one-pot cooking and smoke-cured meat and fish (such as the Arbroath Smokie) are part of the Scottish heritage, there is also a long tradition of fine eating. Steaks are served with sauces made with rare malt whiskies, and many cooking terms have survived from the days of the French alliance hundreds of years ago. Scottish cuisine is varied in its ingredients, flavours and influences.

North East and Yorkshire

Northumberland’s wild and beautiful landscape boasts a dramatic untamed coastline, craggy hills and low-lying plains. A network of rivers weaves through the North East on to Yorkshire’s desolate moors and the famous dales.

The sea has long provided much of the region’s food, for example, kippers have been smoked over oak fires in the pretty harbour of Craster for more than 100 years. Other regional fare includes the potato and cheese supper of pan haggerty (see page 36), one of several recipes that combine vegetables with cheese – which is itself made in numerous dairies across the region. Scones and griddle cakes such as singin’ hinnies (pages 58 and 67) are particularly popular in the region, as is the steamed, lemon-flavoured Newcastle pudding. However, a top favourite is the stottie cake, which isn’t a cake at all: it’s a savoury bread that is great for bacon or chip butties.

Another traditional Northumbrian dish is pease pudding, made using split peas, usually served with pork. Indeed, this meat is probably the best loved in both this region and Yorkshire to the south, where the delicate pink and mild flavour of York ham comes from the dry-salt curing method, which has been exported around the globe. Yorkshire’s countryside features bleak moors, verdant dales and sweeping valleys as well as the industrial cities of Leeds and Bradford and the historic centre of York.

Sheep flourish in the gritty, bleak moors landscape and their milk was made into cheese before it was replaced by milk from the cows who populated the grassy lowlands. It is made into cheese such as tangy, crumbly Wensleydale (traditionally accompanied by apple pie), and is an ingredient in Yorkshire curd tart, an early version of cheesecake.

The Yorkshire palate seems to appreciate particularly dark, rich, sweet goods such as the classic comfort food parkin, a moist, heavy gingerbread made with oatmeal and black treacle, which used to be put in to cook as the bread oven cooled. It can often be found alongside buttered toasted teacakes and the wonderfully named old peculiar cake in the many excellent teashops that flourish in Yorkshire. However, the dish many people think of when the county is mentioned in relation to food is Yorkshire pudding (page 180), a batter of plain flour, eggs and milk or milk and water that was once cooked on an open fire underneath the roasting meat so that it soaked up the dripping juices.

True Yorkshire hosts serve their ‘puddings’ as an appetite-quenching first course, rather than with the meat. Any summary of Yorkshire fare would be incomplete without crediting the county with the finest fish and chips in the land, where the abundant produce of the North Sea is served in crisp batter with mushy peas and chips given extra flavour by being fried in lard. That said, today, the influence of Asian cooking is strong in towns such as Bradford, where folk are more likely to participate in an authentically prepared curry than paper-wrapped fish and chips.

North West

The North West includes the Lake District, Cheshire and Lancashire, taking in the great cities of Liverpool and Manchester. From the tarns of Cumbria to the grassy plains of Cheshire there is a wealth of fantastic scenery and superb food.

Most of the traditional dishes are clearly developed to be suitable for feeding hard-working people who have to cope with a bracing climate. Many meat dishes would be made with lamb because so many sheep graze on the hills of this region. A typically robust meal would be Lancashire hot pot, a lamb stew incorporating the potatoes and other root vegetables grown so widely in the area.

Similarly appealing to the thrifty is tripe, which is a cow’s stomach lining, usually served with onions, and black pudding, an earthy dish made from blood and oatmeal with many variations, all claiming to be the best. The famous long Cumberland sausage is another dish that uses the less appealing parts of an animal so that nothing is wasted. The sea, lakes and rivers provide more delicate flavours, such as the shrimps of Morecambe Bay (page 40) and stuffed herring and trout, which are caught on the line and increasingly farmed in the region. A real local speciality is the mild-flavoured char (page 105), a relative of the salmon, which got left behind in the Lakes after the Ice Age.

This region also boasts two of the finest British cheeses: Cheshire and Lancashire. White, crumbly Cheshire is mentioned in the eleventh-century Domesday Book and was the only cheese that the British Navy would stock on board in the eighteenth century. Lancashire is creamier and is regarded as one of the best cooking and, especially, toasting cheeses as it melts into a velvety mass when heated. If you’re fond of a cheese sandwich, large wholemeal flour bread rolls, or baps, are popular in the region, being an ideal way to eat in a hurry. They are also known as ‘barm cakes’ after a Lancashire word for the froth on liquid that contains yeast.

Similarly long on history are Eccles cakes, small, flat, raisin-filled pastries, which date from at least the eighteenth century. They are closely related to the larger but equally convenient sweet, hand-held and fruity Chorley cake. Another great Northern comfort food is gingerbread, closely identified with the Lake District village of Grasmere. It is usually a crisp spicy biscuit and therefore offers a contrasting texture to the more moist parkin cake that originates across the Pennines in Yorkshire.

Simnel cake (page 178) is now closely identified with Easter, but one early version of it was known as Bury simnel cake at a time when it was traditionally a gift taken by serving girls returning home on Mothering Sunday. Its link with Easter probably stems from the 11 pieces of marzipan used to decorate its top – one for each true disciple.

Finally, have you ever wondered where the Liverpool term ‘scouser’ comes from? It seems to be from a popular Merseyside dish rather like Irish stew, which was similar to a Scandinavian dish known as lobscaus. The stew became known as ‘scouse’, and use of the name broadened to mean a local person.

Western England

The shire counties are sometimes known as the Heart of England and certainly the rolling Malvern Hills, the honey-stone Cotswold cottages and the orchards seen in these western regions are quintessentially English sights.

The region is a foodie’s delight for every year the Ludlow Food Fair highlights the huge variety of excellent fare on offer. The warm, moist climate and rich, heavy soil create fertile conditions for fruit and vegetables, while the grassy hills have long been populated by sheep, which provide meat and wool for the weaving industries.

But it is dairy farming in this region that provides ingredients for its well-known chocolate bars and yogurt desserts. Also renowned are its cheeses, such as the golden Double Gloucester, excellent in a variation of Welsh rarebit called Gloucester cheese and ale (page 34), where cheese and mustard are baked in brown ale. Land where cows graze happily will also fatten beef cattle and this region hosts the famous white-faced Hereford breed, which produces meat of great flavour and tenderness. The sheep that graze the Cotswold Hills have inspired many lamb dishes, including the curiously named Gloucestershire squab pie, which blends the meat with spices and apple, and the equally misleading Oxford John steak (page 124), which is actually leg of lamb with capers.

Other popular meat dishes in this region are faggots (originally made from offal with herbs and spices) and the beef-based Warwickshire stew. However, pork is the meat mainstay, perhaps because pigs once did the job of removing.

the windfalls in the apple, pear and plum orchards of this region. There is even a ‘Midlands cut’ of bacon, and a dish popular on the borders of the Welsh Marches is loin of pork with cabbage cake.

While we’re on the subject of cake, there are several notable recipes from Western England. Brandy snaps (see page 71) and gingerbread are both local favourites. Staffordshire fruit cake is a well-known recipe made extra rich with the addition of black treacle and brandy; there is also a spiced Oxford cake and, best known of all, the Banbury cakes originating from that north Oxfordshire town. These are made from puff pastry filled with raisins and dried fruits.

Other eponymous recipes include Shrewsbury biscuits (page 77), which are rather like shortbread, Coventry God cakes (a traditional christening gift from godparents) and the great favourite of Staffordshire, oat cakes, which are closer to pancakes than oat biscuits and can be eaten with sweet or savoury accompaniments.

No review of the food from this area can omit mentioning the famous Worcestershire Sauce, a liquid that adds flavour to almost any savoury recipe and which originated when the Governor of Bengal returned to his native Worcester and tried to re-create an Indian recipe. The sauce was a complete disaster until tasted after several months when it had matured into the fine ingredient still used today.

Similarly bizarre is the heritage of Cooper’s Oxford marmalade, which is famous for its chunks of bitter peel from a variety of Seville oranges grown in Andalusia. Apparently, hardly anybody else can use the fruit because it’s so bitter!

Eastern England

Go east across England and the landscape becomes flatter as the horizon slips into the distance. This is a land of wide spaces and cinematic skies and is home to the arable farmlands of Britain. The climate is perfect for a wide range of crops and animal rearing.

Our journey starts in the east Midlands counties of Derbyshire and Leicestershire, where high levels of dairy farming have stimulated the development of great cheeses such as flaky, tangy Red Leicester, green-tinged Sage Derby and creamy Stilton. This last takes its name from the village where an innkeeper first served the open-textured cheese to visitors, although, in fact, it was apparently made by his brother-in-law miles away in Melton Mowbray. This ‘King of Cheeses’ is delicious on its own, but can be used also in hot or cold recipes.

Wander on eastwards and we reach the fertile, wide fields of Lincolnshire where early vegetables and crisp celery burst from the soil. We can range through more vegetable fields as we travel south and pause to admire the gooseberries and gages (delicious in fruit tarts) of Cambridgeshire. This fertile region, sometimes called ‘the food basket of Britain’ produces cereals, flowers, fruits and vegetables. Notable recipes include celery baked in cream, the bacon and apple-filled fidget pie (page 121), and Trinity College pudding (page 150), an early version of the Christmas pudding.

The land is noticeably flatter as we head across the reclaimed fertile earth of the Fens to the Norfolk Broads. The mild climate stimulates farming of soft fruits such as strawberries, redcurrants, raspberries and blackcurrants, which create the wonderful deep reds and tender pinks of a summer pudding.

Here rabbit stew and jugged hare were once popular choices for those who could not afford beef and lamb. Nowadays, though, Norfolk is famed for its huge production of turkeys, including the famous Norfolk Blacks. However, the fields of wheat, barley and rye and the flat fens host many game birds such as partridge, quail and woodcock.

One notable Norfolk speciality is samphire, a juicy marsh plant sold all across the area. When boiled or blanched it tastes like slightly salty asparagus. This, of course, brings us to a more widely enjoyed seasonal crop: asparagus, served with hollandaise or white cheese sauce.

In days gone by, the port of Great Yarmouth would become so full of fishing boats unloading herring that it was said you could walk across the harbour just by stepping from deck to deck. The boats are gone but the smokehouses now cure red herrings and bloaters, mainly for export. However, grilled Norfolk herrings can be matched with another local crop, the yellow English mustard grown around Norwich, for a zingily spicy meal.

All along this Eastern coast are villages specialising in harvesting the sea for some of its produce, such as cockles and whelks. The best example is Cromer, where the dark meat of the small but succulent crabs is considered a great delicacy as used in recipes such as baked Cromer crab.

South East

The South East of England benefits from a warm, moist climate and fertile soil, allowing its farmers to grow and raise almost anything, which is just as well, because the ever-expanding capital city of London has an enormous appetite.

The lush green county of Kent has long been known as ‘The Garden of England’, and the rolling hills of Sussex and the plains of Hampshire are farmed extensively too. All of these counties border onto the English Channel, which is a valuable source of an enormous variety of fish and shellfish.

Many varieties of apples, pears, plums, cherries (introduced by the Romans) and soft fruits have been cultivated in Kent since at least Tudor times. This may have influenced the region’s love of a pudding: there are hundreds of Kentish desserts, many incorporating fruit or the locally grown hazelnuts, also known as Kentish cobnuts. One creamy favourite is Kentish pudding pie (page 160), which is similar to a baked cheesecake.

The neighbouring county of Sussex has a quintessentially English steamed pudding named after it. Sussex pond pudding (page 158) is made with butter, brown sugar and lemon in a suet pastry case, the delicious dark oozy contents earning the dish its name. Substitute dried fruit for lemon, and the name changes to Kentish wells pudding. Other famous sweet fare from Sussex include lardy Johns and Sussex heavies. Across the border, Hampshire offers an equally intriguingly named dessert in the form of friar’s omelette, in which the soft flesh from baked apples is mixed with spices and egg yolk before being baked until set firm.

The coastline that surrounds the South East, together with the rivers that weave across it, provide an enormous amount of fish and shellfish. It is well known that oysters were once so ubiquitous that only the poor bothered to eat them, but other freshwater produce included eels and trout, while the sea offers shellfish, the delicate Dover sole and other flatfish.

What was once transported to be sold from London’s fresh food markets now travels in to meet the capital’s need for food. The abundant choice of the city’s restaurants allows you to choose authentic fare from all around the globe. Whatever you are looking for, you are bound to find – and with a choice.

Finally, several dishes from this region rejoice in famous names. The strawberry, meringue and cream of Eton mess (page 148) was created for visiting parents to picnic on, while Boodles orange fool (page 146) gets its name from the St James’s club where it originated. London particular (page 30) is a pea and ham soup created by chefs at Simpson’s in the Strand and named using the term for London’s smog coined by Charles Dickens in his novel Bleak House. Brown Windsor soup bears the name of the royal castle in Berkshire.

South West

Think of the West Country and, for most of us, the mind turns to cream teas, seaside meals and cider. This tapering peninsula is warmed by the Gulf Stream, which makes the sea more welcoming and the climate so temperate that even tropical plants survive here.

Seafood is big business in Cornwall. Fishing boats set out for two seas from the long coastline and return with sardines, mackerel, monkfish, grey mullet and hake, as well as shellfish, crabs, crayfish and lobsters. The stargazy pie immortalised in children’s books had pilchards’ heads peeping out through the crust of the topping. Sadly, this evocative dish is rarely cooked today as the supply of these fish has become very erratic in the region.

The moors inland also host a variety of wild game such as rabbit and duck. The idea behind the ubiquitous Cornish pasty (page 50) was that the tin miners could hold it by the outer crust as they carried it to work, making it one of the earliest known fast (but certainly not junk) foods. What makes the Cornish pasty different from other pasties is that the ingredients were wrapped raw and then were subsequently cooked inside while the pastry was baked.

Moving northeast we arrive in cream tea heaven: Devon, where clotted cream is served with scones and a pot of tea. The county is also known for light yet rich little buns called Devonshire splits (there is a Cornish variety too), made using cream instead of milk.

The next county, Somerset, is the birthplace of the most famous cheese in Britain, the Cheddar, where it was matured in the caves of Cheddar Gorge from the fifteenth century. This creamy cheese can be flavoured from mild to strong and most of us reach for this variety when we need cheese for cooking purposes. It is also the basis for the ploughman’s lunch (which was never actually eaten by ploughmen, but was a clever marketing device dating from the 1960s).

Cheddar’s traditional companion, an apple, is also widely used in Somerset cooking (especially with pork) and, of course, can also be allowed to ferment into cider, another excellent cooking ingredient with pork and turkey. Somerset dairies also now produce the ‘Queen of Cheeses’, Brie, known for its smooth yet tangy taste and its lovely aroma.

If you are looking for an unusual recipe to drop into the conversation, try something from the next county to the east: Dorset. Choose between rook pie, a cheap dish for labourers, or the definitely more upmarket cygnets stuffed with beef, roasted in a flour and water paste. Dorset also has an interesting line in soups, including some made from lettuce, green peas or cabbages. Another old recipe (apparently dating from Victorian times at least) is for beef olives, which consist of thin sliced steak wrapped around a stuffing.

Finally, in our journey through the West Country, we reach Wiltshire, home of the lardy cake, named after the refined pig fat that gives delicious flavour to the white bread dough, sugar and dried fruit with which it is baked.

Wales

Wales is proudly different from neighbouring England, preserving its own language and culture. From harps, choirs and daffodils to the particular charms of the rugby pitch, Wales has many an icon to savour.

Over the centuries Wales has developed a simple and wholesome cuisine that reflects its sometimes challenging terrain and the tough demands of historic industries such as coal mining and steel making.

Much of the mountainous northern landscape can only sustain hardy oats and sheep, and these two ingredients appear in many guises in Welsh cooking. The southern terrain of valleys and rolling hills supports beef and dairy cattle and a wide variety of fruit, vegetables and cereal crops.

The meat most identified with Wales is lamb, its sweet flavour enhanced by mint, honey or lemon. However, beef cattle are also widely raised, and the traditional meat mainstay of the Welsh diet is the pig. Bacon appears in many Welsh recipes and indeed combines with lamb and sometimes beef as well in the famous dish called cawl. This is a classic one-pot meal (the word means ‘broth’ or ‘soup’) in which bacon is added to lamb scraps in a stock made from vegetables such as cabbage, swedes and potatoes. The national symbol of Wales, the leek – which, ironically, is not widely grown in the Principality – is sometimes added in small slices just before serving in one of the many variations on this hearty stew. Some families eat the soup with just vegetables in as an appetite-reducing first course before serving the meat element of the meal, and it is traditionally eaten with a wooden spoon.

Vegetables also feature heavily in the curiously named Glamorgan sausages (page 37), which are actually meat free, being a mixture of grated cheese, breadcrumbs with herbs and chopped leeks or onions. This thick paste is bound with egg and then rolled in flour to make sausage shapes, which are then fried and served with potatoes.

Cheese is the basis of another Welsh mainstay, Welsh rarebit, which has been adopted nationwide as a quick and easy snack. The simplest version is slices of cheese melted onto toast, but there are countless variations using a creamy blend of cheese with milk or cream plus butter or ale.

Just as leeks are more commonly grown outside Wales, so its most famous cheese, the crumbly and salty Caerphilly is now mainly produced over the border in the West Country. However, Welsh dairies do produce a range of cheeses including goats’ cheeses and some fine Cheddar.

The seas and rivers of Wales host a range of fish, including the sewin (Welsh for sea trout), traditionally baked wrapped in bacon (page 103). However, one of the most noteworthy products of the sea is the edible seaweed harvested and used to create an unusual breakfast dish. Laver is collected from the rocks, washed and boiled for hours to form a purée, which is mixed with fine oatmeal to form small cakes that are fried in bacon fat.

Finally, there is a wealth of tea-time treats in the list of Welsh fare, from oven-baked bara brith (page 76) to melt-in-the-mouth delicacies from the griddle such as Welsh cakes and crempog, which are very rich pancakes made with buttermilk.

Recipes and page numbers refer to the Around Britain cookbook.

Recipes and page numbers refer to the Around Britain cookbook.

Head of Dairy Diary; I’m passionate about producing high quality products that our customers will cherish. I’m also a mum of three and I enjoy cooking, walking, gardening and art with my family, as well as lino printing (if I find time!)